[This piece originally appeared in SURFER magazine Volume 60, Issue 2 back in 2019.]

It’s really hard to measure the impact of a single individual on our sprawling mass of a surfing culture. Yeah, Kelly Slater sold a million pairs of boardshorts and Tom Curren taught us what it meant to live as a high-performance soul surfer—though, hell, Duke Kahanamoku is technically responsible for all of our surfing lives in the first place, so his impact is actually pretty easy to measure. But for every marquee name in the surfing hall of fame, there are countless, less-heralded geniuses that have touched our surf lives in ways just as meaningful and impactful.

Rick Griffin is one of those geniuses.

A bear of a man, tall, broad-shouldered, occasionally bearded and imposing, Griffin is best known in our surfy universe for creating the Murphy cartoon character—that tow-headed, perma-stoked gremmie, always shouting “COWABUNGA,” who inspired countless rip-offs and schoolbook doodles. Murphy first appeared in SURFER in 1961, not long after Griffin met SURFER founder and fellow cartoonist John Severson, who recognized the talent of the then 16-year-old Griffin and convinced him to pen a column for his new magazine.

After first publication, Murphy was one of us. A cartoon character, sure, but the Murph was a transcendent piece of art far more than a simple illustration. Murphy was a perfect stand-in for the wide-eyed exuberance surfing tends to produce in those of us hopelessly dedicated to the sport, a spirit that was practically buzzing through the entire country in the surf-mad early ‘60s.

Like any good work of art, Murphy was a reflection of both the culture he was part of and of his creator. When Griffin first unveiled Murphy, they were both teenaged, “aw shucks, ain’t this swell” kids, just stoked to be there, riding waves and having adventures. It was his naive, fun-loving, harmless rebellion

that made Murphy a logical choice for SURFER’s mascot as well as local bands who plastered his face on their posters advertising gigs throughout Southern California.

But Murphy changed right alongside surf culture and Griffin himself. By 1964, Griffin was in his 20s, beginning to grow bored of Southern California and running out of ideas for Murphy. Drawn toward the burgeoning counterculture in San Francisco, Griffin was making regular trips north, expanding his horizons, his mind and his art. In the mid-to-late ‘60s, Griffin had moved to San Francisco and cannonballed into the spaced-out hippie scene. So did Murphy. So had surfing itself.

The above profile of Griffin, written not long after Griffin’s death in 1992 by longtime SURFER writer Steve Barilotti, walks the reader through the profound changes both the artist and surfing experienced in the ‘60s and ‘70s.

“Rick’s art had changed radically too. It became more sophisticated and worldly: dense, ornate imagery surrounded by loads of filigree and flowery mandalas,” Barilotti explained. “This was 1966 and Rick was definitely part of the pharmaceutical vanguard. Over the course of a year the face of surfing began a subtle change from the clean-cut Jantzen boys into shaggy, underground wave mystics.”

In San Francisco, Griffin’s art fit in perfectly with the flowering hippie movement. He was commissioned to produce poster art for “Be-Ins,” sort of the 60s, drugged-out versions of TED Talks with music provided by The Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane.

“Rick, like the rest of us, was on a mission to turn on the world,” recalled Jerry Garcia [ed’s note: yes, that Jerry Freaking Garcia] in Barilotti’s piece. “I dug Rick’s stuff because it related so well to my own psychedelic experiences.”

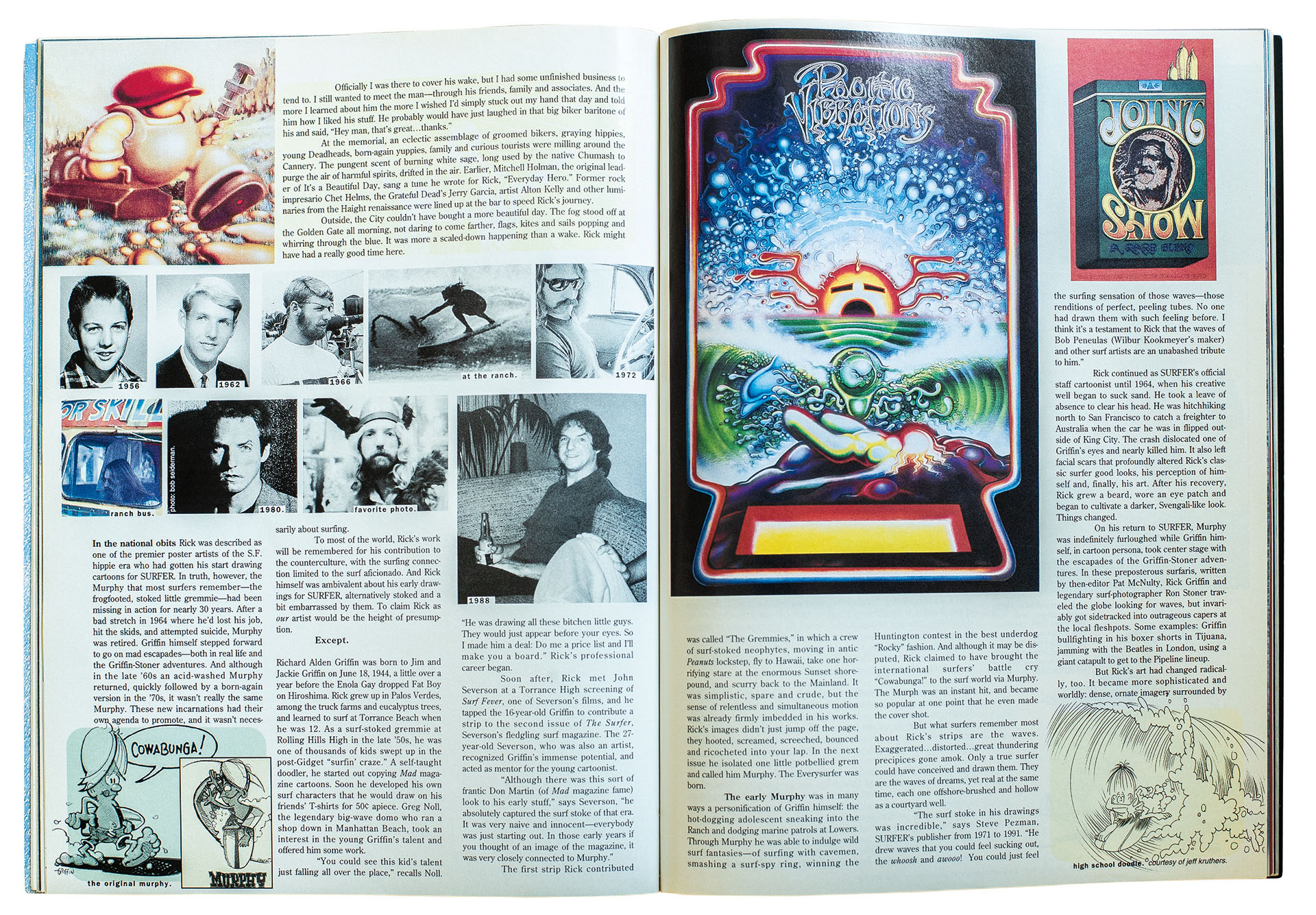

Griffin took what he learned from the San Francisco scene when Severson later asked him to produce the cover art for his surf film masterpiece, “Pacific Vibrations”. The image Griffin dreamt up for the film was mad psychedelic beauty. Possibly his best-known work. A yawning sun like an Aztec god setting into the sea, an A-frame of glassy tubes with dolphins riding inside, the nude faceless form of a buxom woman

lying in the foreground. It was the entire hippie surf scene captured in one dreamy painting.

Murphy reappeared in SURFER in 1969, like Griffin, and surfing itself, transformed by the expansion of spiritual possibilities in the late ‘60s. No longer a squeaky-clean gremmie, Murphy rode waves wearing Hopi Indian masks and transmogrified into eyeballs burning in flames. Griffin and Murphy flirted with born-again Christianity, with a euphoric Murphy reciting scripture in comic strips.

By the ‘80s, Griffin was contributing less to SURFER, and spending lots of time riding big waves and big motorcycles in northern California. Murphy had run its course, replaced by the clumsy, poor-surfing “Wilbur Kookmeyer” character, a clear reference to the overcrowding that was beginning to plague the sport. Griffin was killed in a motorcycle wreck in 1991.

His legacy is one of expansion—both of his own mind and what surfing, surf art and surf culture could be.

Original Post from this site