Any person who hasn’t been keeping up with the ebb and flow of the pro circuit would be forgiven for rolling their eyes and cynically chalking up the “hybrid pipe” movement as an effort to jump on the eco-friendly bandwagon. Although, that isn’t to say there isn’t an element of sustainability being sought as it relates to the current existential challenges facing halfpipe riding or if it is as “cool” as it once was.

Depending upon which mainstream media spectacle you are tuning in to, Dew Tour, US Open, X Games, etc., hybrid pipes go by many different monikers including “pipestyle” and “modified pipe.” Regardless of how they’re branded, each seeks to combine the traditional vertical elements of a transitioned wall with jumps, jibs, highways, hips, and other features to freshen up a largely stagnant pipe scene. – Pat Bridges

Andy Hetzel

Danny Davis, Dew Tour 2020. Copper, Colorado.

Catch 22

The fact of the matter is that halfpipe snowboarding as a spectator sport hit a high mark in 2010 at the Vancouver Olympics, where Shaun White, having perfected a plethora of never-been-done double corks in the lead up to the Games, not only grabbed his boot, but he also grabbed unprecedented network TV ratings, the highest in Winter Olympic history. Yet by linking back-to-back-to-back double corks, the record-setting audience who tuned in to see his historic, gold medal-winning performance may have ultimately tuned out. Let’s face it, nothing about top tier halfpipe competition at the pro level is fathomable by the average rider. Even the pipe itself, an iced over, two-story-plus behemoth, is prohibitively intimidating to the lay person. Fast forward to the winter of 2020, slightly less than a decade after Shaun White ascended the Vancouver Olympic podium in front of more than 30 million NBC viewers. Less than ten 22-foot superpipes were built at ski areas in North America, down from a peak of around two dozen in 2010. This is in stark contrast to the late 90s heyday of halfpipe riding when some industry experts like Mike Bettera, president and CEO of Effective Edge, a company dedicated to enhancing the winter resort experience, estimate that 75% of ski areas in the United States had a public pipe of one size or another. Standouts like Mammoth Mountain, CA and Timberline, OR had as many as five rideable pipes at the same time! Bettera elaborates, “If you walk around any ski hill in the summer, odds are that somewhere you will see two parallel piles of dirt stretching for hundreds of feet. These are the earthworks still there from when that spot had a halfpipe.”

Breckenridge, Colorado.

Ben Ferguson, Peace Park, 2016. Grand Targhee, Wyoming.

Brandon Davis, Peace Park 2016. Grand Targhee, Wyoming.

So what happened after Y2K to soften the saturation of halfpipes at ski resorts? Rather than a singular cause, this attrition is likely the result of a myriad of factors. With the advent of 18-foot pipes being heralded by an American sweep of the Olympics in 2002, bigger airs and more technical, higher-degree spins became celebrated. This left the stylish head-high tweaks that seemed larger than life while plastered on the bedroom walls of the 90s, no longer considered relatable aspirations. Meanwhile below the lip, just dropping into a competition-ready transition left even the most fearless weekend warriors puckered and deflated. Concurrently, ski area accountants introduced the concept of return on investment into budget meetings, leading many resorts to realize they either didn’t have the resources, customer base, or stomach to enter the fray in what was becoming an ever escalating game of one-upmanship in terms of who could build the biggest halfpipe. Liam Griffin is arguably the most experienced event organizer in the history of snowboarding, having spent more than a decade overseeing the Burton Global Open series as well as serving on the Ticket to Ride World Tour board. Since then, Liam has produced several Red Bull Signature Series contests and most recently partnered with Travis Rice as a co-founder and chief operating officer for the upcoming Natural Selection off-piste showdowns, which aim to entirely upend the status quo when it comes to freeride contests. During his tenure with Burton, though, Liam was front and center when halfpipe proportions began to become ever more exaggerated. Liam explains, “I definitely had concerns. Going from 18-feet to 22-feet took halfpipe riding from something everybody could enjoy to something that only certain people had access to. I’m not going to say any names, but there were also a lot of established riders who weren’t down with that development.”

Danny Davis, Peace Park 2016. Grand Targhee, Wyoming.

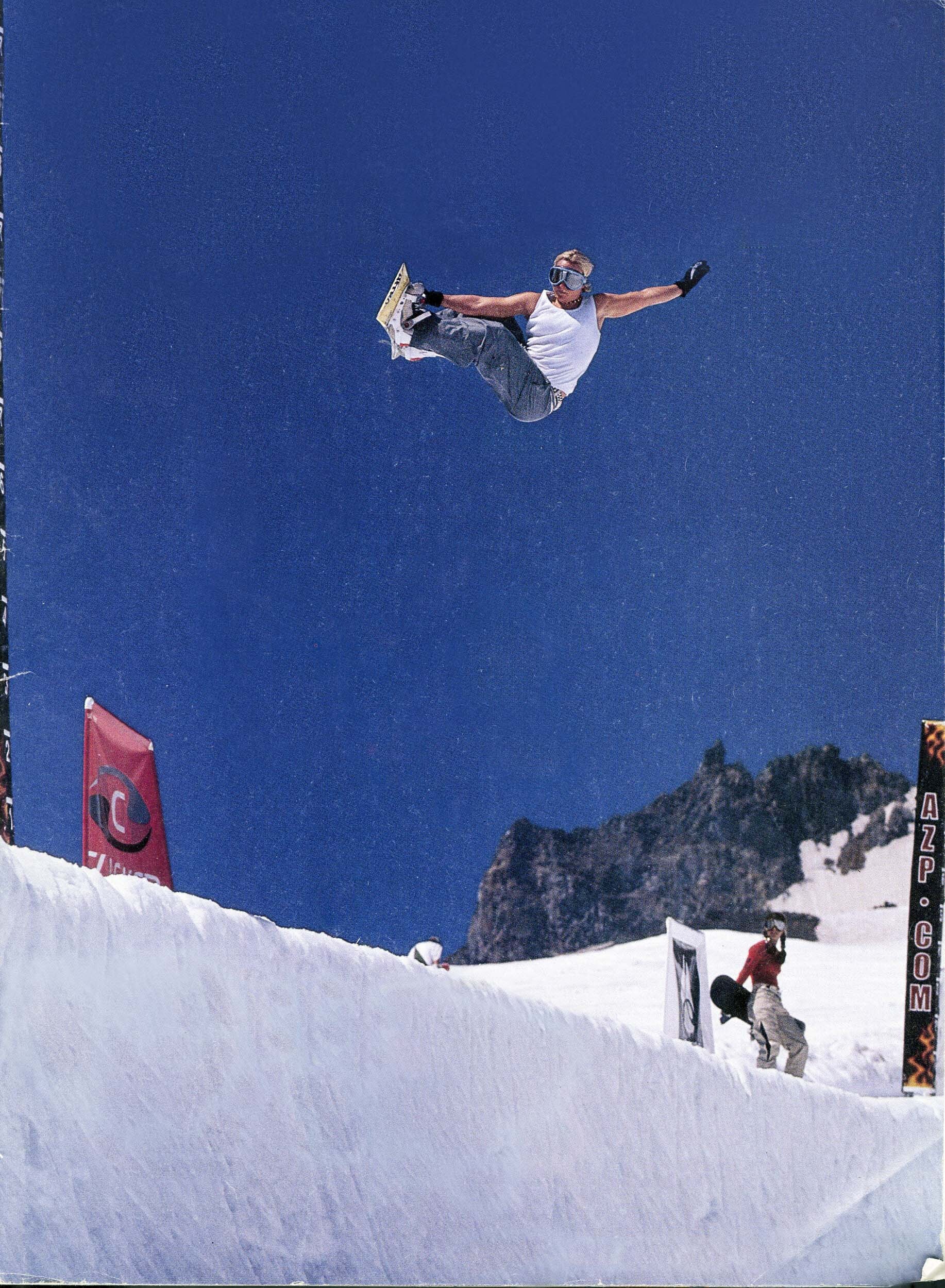

Nicola Thost, Mount Hood, Oregon. 1999.

These circumstances coincided with jibbing experiencing a renaissance, particularly in terrain parks, and those same ski area bean counters advocating that an investment in rails, boxes, wallrides, and other freestyle features that don’t melt at the end of a season was a more fiscally prudent path than pushing a pipe. Consequently, the introduction of slopestyle as a medal event at the 2014 Sochi Olympics accelerated a brain drain of prodigious talent, since every mountain that once had a pipe, still had a park. Therefore, with a few exceptions, contest organizers no longer had a pipeline of high-profile wunderkids like Louie Vito, Kelly Clark, Terje Haakonsen, and Danny Kass to evangelize the cause. The result of all of this is that halfpipe riding is quickly becoming a hyper-specialized discipline that is only relevant to those who are dedicated to the competition side of it, like aerial free-style skiers or speed skaters, or even parallel giant slalom snowboard racers! To that end, the Winter X Games, our sport’s version of the Olympics before, well, the Olympics, is attempting to reboot what was once their main draw by adding best trick sideshows and pivoting to a jam format. Lest anyone doubt the stakes at play, remember that vert skating ruled the Summer X Games roost until it didn’t, and in 2008, ESPN decided to cease including the event on its schedule. As an aside, currently the Winter X Games discipline achieving the highest Nielsen Ratings is the Knuckle Huck, pointing to the audience’s affinity for accessible action.

The Learning Curve

So why are the organizers of the Dew Tour and US Open championing hybrid pipes as the next chapter in halfpipe competitions? Well, to many, these events are actually behind the curve and playing catch-up. Going all the way back to 1989, the TDK World Championships in Breckenridge, CO featured two-foot-tall tombstones on the first hit. Further west at June Mountain, CA, the inaugural OP Pro put two large booters at the bottom of their venue to allow contenders one last chance to bag big air in their runs, albeit on a different trajectory. That same season, hand-dug ditches in locales like Jackson Hole would be the scene of sessioners using logs and other found objects to mimic coping on the vert.

Maddie Mastro, Dew Tour 2020. Copper, Colorado.

In Oregon, in the summer of ’92, Kurt Heine fabricated an elevated jib out of wood and metal that was anchored on the rollout deck, enabling railslides and stalls two feet above the lip. At the same time, photographer Sean Sullivan and a handful of North of the Border boarders bolstered their Blackcomb summer camp bag of tricks by placing slidable metal gates atop the vert. The first contest conceived to deviate from the stock setup was the 1996 UnVailed, which featured several true tabletops dissecting the flatbottom, affording pros like Todd Richards, Kevin Jones, and Dave Downing endless interpretive possibilities. According to two-time US Open champion Todd Richards, “At that event in Vail, it was almost like a double barrel pipe. You could do a frontside air followed by a backside air and then there was kind of a loaf tabletop in the middle you could hit. So yeah, it was definitely the first pipe where you could combine hitting walls and jumping in the same line.” A decade later, Mammoth Mountain’s first Fiesta de la Pipa would see wallrides, tubes, tombstones, and even piñatas dangling above the deck, and across the Atlantic at the Arctic Challenge in Scandinavia, Terje made hip takeoffs the preferred way to start every run at his signature showcase. Rightfully so, many point to former Olympian and X Games champion Danny Davis and his Peace Park as the true catalyst for this movement, but his advocacy goes all the way back to 2012 and his first Peace Pipe gathering at Northstar, CA, which incorporated a myriad of gaps, flat bars, and extensions placed among the 22-foot walls. “For me, it was a boredom thing,” explains Danny about his motivation behind coming up with a whole new take on transition riding. “At contests and shoots, it was always the same halfpipe all season long, year after year. Peace Pipe was an exploration thing. We were all ready for something fresh. I also think part of it was that on a bigger level, I feared for halfpipe riding, like skaters probably did for vert at one point.”

Scotty James, Dew Tour, 2020. Copper, Colorado.

Once Peace Park, which was made possible with subsidies from Mountain Dew and Burton, proved that there could be corporate support for these type of tangents, Red Bull injected their Double Pipe side-by-side halfpipe experiment, complete with pass-through sections, a-frames, rail transfers, and ramped takeoffs, into their Signature Series in 2015. The Double Pipe was one of the contests which Red Bull tapped Liam Griffin to produce. “This event really added an element of surprise of the unknown into the mix,” Liam recalls. “Because when a rider approached a wall, you never knew if he was going to go up and air and re-enter or go straight over the top.” These are but a handful of examples of when and where the tried-and-true halfpipe venue has been tinkered with throughout the years. Furthermore, pipe-cutting implements have now become an everyday tool in most public parks. Radial snow-sculpting machines like the Pipe Dragon, Monster, Scorpion, Magician, Global Cutter, Zaug, and HPG, which connect to or are towed by snowcats, are not only used to expand the trickable possibilities of the terrain, but they also provide a practical way to clean up uneven refuse left over from building tabletops and whatnot, thereby making every pile of snow ripe for a rippable transition.

Shape of Things to Come

What we’ve seen the past few seasons with these deviations at contests like the Dew Tour and US Open can best be described as a work in progress. For every viral-ready clip captured in the finals, there are entire runs that are nowhere near ready for primetime viewing. But remember that conventional halfpipe riding encountered the same growing pains for nearly two decades with pros, spectators, and pundits, alike, ironically championing cookie-cutter consistency from one wall to the next. In the 80s, legends like Jeff Brushie, Craig Kelly, Shaun Palmer, Terry Kidwell, and Todd Richards were constantly having to figure out different setups, with each having been purpose-built specifically for that competition alone, in order to determine a way to apply the tricks they already knew how to do. Oftentimes, once they had dialed their run, the finals would be over, and it was off to the next tour stop to start the process all over again from scratch. This made progression incremental, which begs the question of whether or not some form of standardization might help hybrids become more accepted? And this dilemma isn’t isolated to the future of halfpipe riding, alone. The same sameness that plagues pipe is quickly becoming a thorn is the side of slopestyle, since their inconceivable trick trajectory and linear courses are quickly alienating their audiences, too. Hence the aforementioned Knuckle Huck phenomena. Perhaps, rather than injecting jumps and jibs into another aspect, consideration should be made toward completely combining the disciplines of slopestyle and halfpipe altogether. In turn, that could lead to the ultimate manifestation of the ideals that have brought us into the era of hybrid pipes in the first place and possibly provide the solution to more than one challenge, while helping to fuel progression and inject new energy into the contest scene as a whole.

More from SNOWBOARDER Magazine here.

Original Post from this site