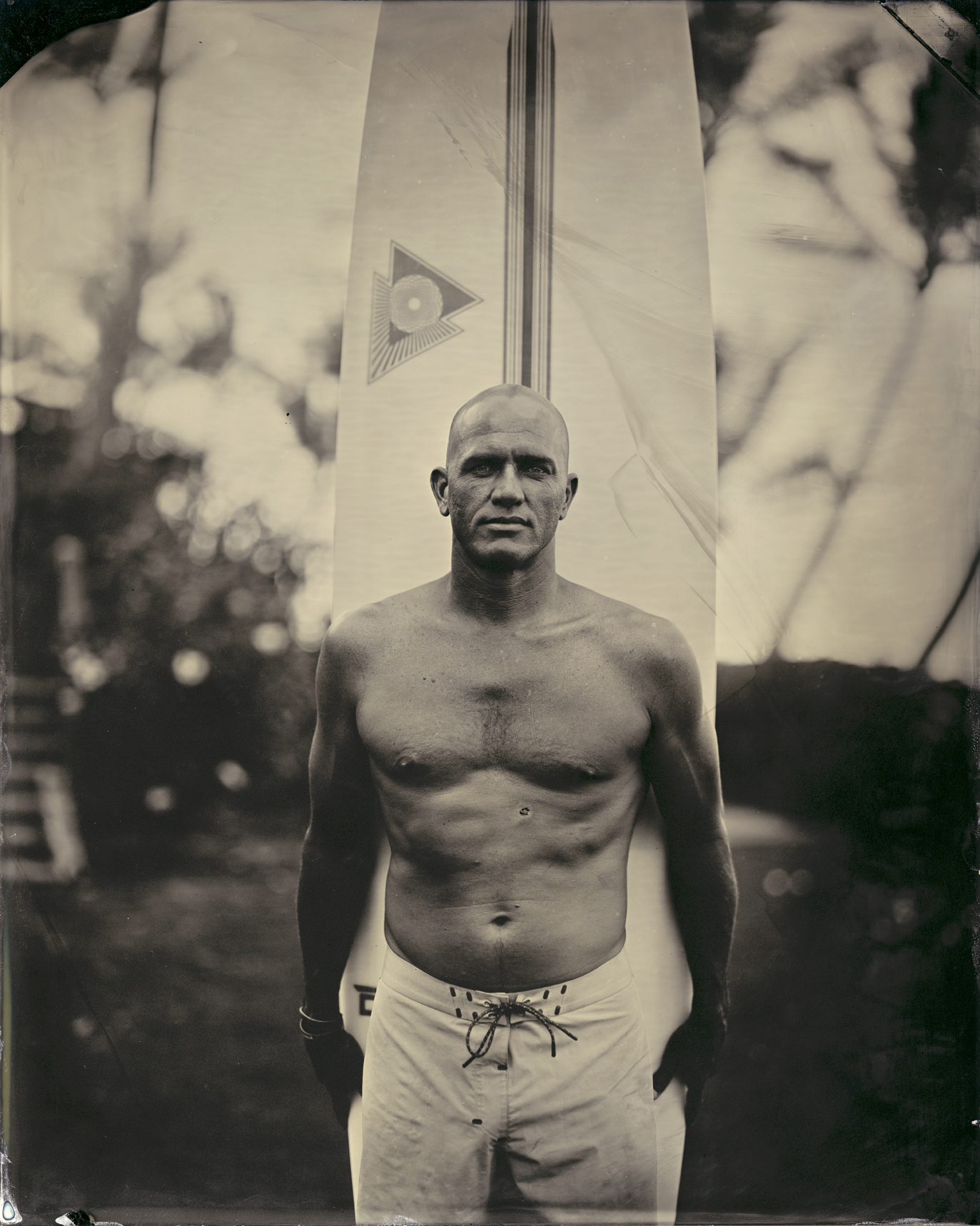

Kelly Slater stands in the backyard of his home on the North Shore of Oahu, holding perfectly still for the camera. He’s barefoot, wearing a pair of boardshorts and is holding a big-wave gun upright behind him. At first glance, it seems like just another photo shoot for the most popular surfer in the world, but the photographic equipment situated in front of him isn’t exactly the high-tech digital gear you normally see surf photographers carting around.

Getting settled behind a tripod with a large, wooden field camera affixed to the top of it is Brooklyn-based photographer Joni Sternbach, who’s spent the past decade creating antique-looking, large-format portraits of contemporary surfers. Sternbach is one-part chemist, one-part photographer, using a process called wet-plate collodion—an early photographic technique from the 1850s— that makes modern subjects (like an 11-time World Champ holding high-tech Tomo gun) look like a historical figure from the Civil War era.

The process of creating these striking images is much more laborious than simply loading a memory card and firing away. Whether she’s shooting in someone’s backyard or on the beach, Sternbach sets up a portable darkroom—a taped-up, three-ply cardboard box—that sits on a folding table nearby. First, she takes a thin, 8″ x 10″ tin plate and coats it in the gooey, sticky collodion, then sensitizes it in a tank of silver nitrate to create a light-sensitive medium. She then loads the plate into the back of her camera, makes an exposure (which requires Slater and the rest of her subjects to remain completely motionless) and returns the plate to her homespun darkroom.

Sternbach likens the process to a performative art or a magic trick, as the next step usually draws a crowd of spectators. After developing the photo in the dark, she rinses it and places it in a fixer bath. Now in the daylight, the photo slowly changes from a negative to a positive and Slater’s sepia-toned face gradually comes to life. If it weren’t for the Tomo logo plastered on the front of the board, one could easily be fooled into thinking this was a photographic artifact from the early days of surfing.

“I like to call it the Polaroid of yesteryear,” says Sternbach. “The beauty of those reactions, that’s gold. What really drives the project is the participation and the community aspect involved.”

While Sternbach has always had a fascination with the ocean, she didn’t know much about surfing until the early 2000s. One day, while shooting with film from a bluff in Montauk, she took a photo of a lineup filled with surfers and instantly felt a connection. Shortly after, while messing around with her wet-plate collodion setup on the same bluff, she spotted a lone surfer making his way out to the water and asked if she could take his portrait. “That one picture made me think, ‘Oh yes, this is definitely going to work,’” says Sternbach.

Sternbach has since taken her specialized camera and DIY darkroom to beaches all over the world, capturing an eclectic mix of wave-riders, from everyday Joes to icons like John Florence, Jordy Smith, Donald Takayama, Kassia Meador, Shaun Thomson and the Malloy brothers. The result has been an on-going project titled “Surfland,” a series of faux-antique photographs that play with the viewer’s perception of time, which has been published in two books and exhibited at The Von Lintel Gallery in Los Angeles.

Last winter, Sternbach spent some time on Oahu gathering a batch of portraits as an ode to the island’s rich surf history. “I’ve photographed in Biarritz, California, Australia, England and Uruguay, which all have a lot of surf culture,” says Sternbach. “But photographing in Hawaii was like reaching the Motherland.” According to Sternbach, surfers provide an endless amount of inspiration. “I think of surfers as the new version of cowboys, unconstrained by fences and sprawl,” she explains. “Maybe this project doesn’t have to go on forever, but it could. The groms that you photographed yesterday are tomorrow’s pros. To me, working with this archaic process and photographing contemporary culture is a way of having a conversation about history, about culture, about photography and about surfing.”

[Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in 2018]

Original Post from this site