A 2,000-plus-mile plume of fine red Saharan dust is set to inundate the southeastern coast of the United States this week. While this sounds slightly apocalyptic (especially with its arrival alongside a global pandemic), such events are actually quite common. And, according to various scientists, these giant sand storms can have surprisingly dramatic effects on the Atlantic Ocean.

Beginning in late spring or early summer, a mass of dry, dusty air called the Saharan Air Layer (SAL) usually starts to whip up over the Sahara Desert. It propels a “mid-level jet” of two-plus-mile-thick clouds of dust about a mile high and due west at 25-to-55 miles per hour (or 10-25 meters per second) across the Atlantic to South America, the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, Florida, and sometimes the entire lower 48 states of the continental United States. “Although it is normal to see SAL outbreaks in June & July,” the National Hurricane Center’s Tropical Research and Forecast center tweeted yesterday, “this one is significant.”

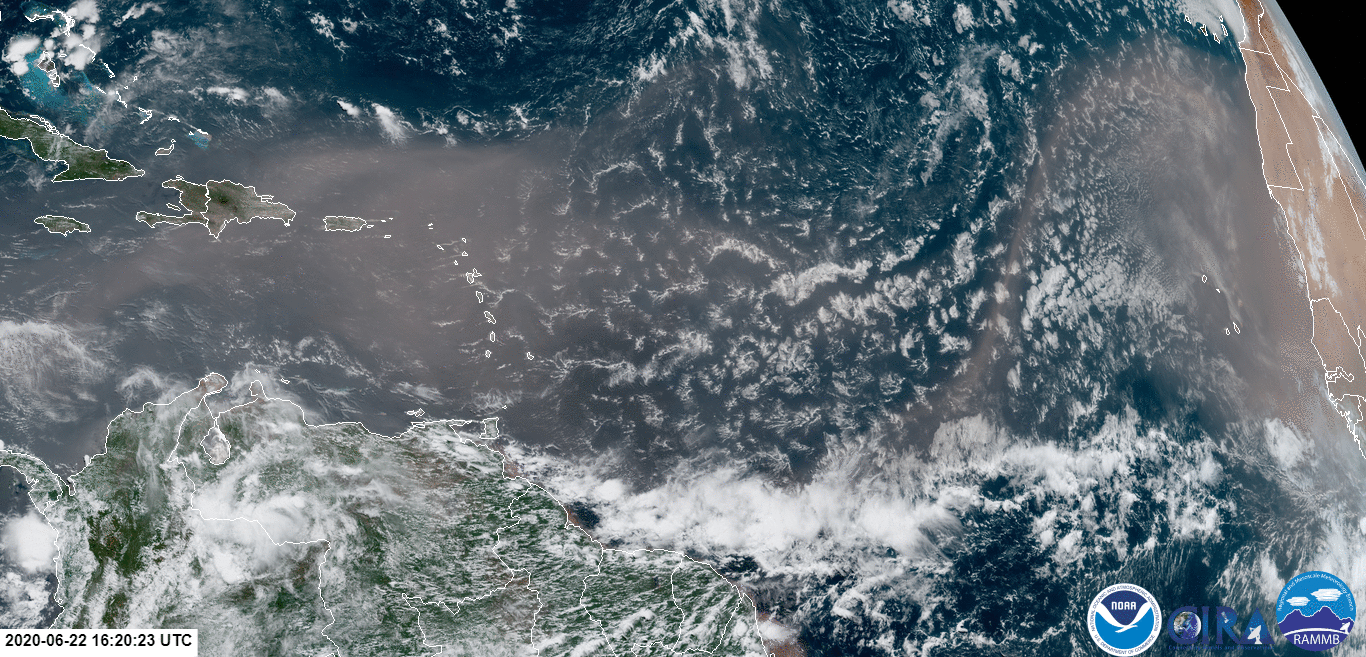

While dust storms aren’t unusual by any means, this one has been generating quite a bit of buzz over the past week for its sheer size. Photos of hazy islands have been circulating online—even astronauts at the International Space Station are posting images on Twitter of a massive, brown dust plume making its way west.

Today’s view of a large Saharan dust plume.

Watch in near-realtime: https://t.co/mtWrgxAxqY. pic.twitter.com/aq4Ozto4Ng

— CIRA (@CIRA_CSU) June 19, 2020

The dust carried in the warm, dry air and the heavy winds associated with the SAL — which bear about 50 percent less moisture than the usual tropical atmosphere does — “can suppress Atlantic hurricane development and activity,” says Dennis Feltgen, a meteorologist and spokesperson for the National Hurricane Center in Miami.

Just a few weeks ago, NOAA announced that the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season is forecasted to be an above-average one this year—so does this oncoming sandstorm change things for the rest of the swell-generating hurricane season?

According to Feltgen, the above storm-suppressing phenomenon only happens at the time the SAL is present. While short-lived, the extremely dry air coming off the desert can not only prevent what would otherwise be impending tropical storm formations, but also weaken existing ones.

“Outbreaks like this affect things over the scale of a couple of weeks as the dust treks across the Atlantic, making the atmosphere locally stable and thus not conducive for tropical cyclone formation,” says Mike Watson, a Florida-based lead forecaster for Surfline. “This is only temporary, though,” he says, agreeing with Feltgen and the NWS, “and one outbreak is not indicative of the overall amount of seasonal [hurricane] activity.”

Just the same, while the effects may be spotty when it comes to tropical storms, they have other, more significant and longer-term impacts: Watson pointed to NASA research that suggests some 30 million tons of iron-rich Saharan dust sprinkles (and feeds) the Amazon basin annually.

That iron-rich sand also appears on the iron-poor soils of Florida, which help crops grow. “On the flip side,” Watson says, “a[nother] NASA study found that the increased iron can help fuel toxic algal blooms over the Gulf of Mexico.” (Unfortunately, such algal blooms can be harmful to coral reef)

The SAL normally starts to taper off in late August or September, which, as it so happens, is when the Caribbean, Gulf Coast, and east coast of the US tend to receive the strongest hurricanes of the season.

Those in the path of the monolithic dust cloud can expect to experience a couple of weeks, give or take, of hot, hazy, hurricane-free weather, and while that may or may not mean less swell for those in the Caribbean and the east coast (Watson and co.’s jury at Surfline is still out on that matter), it also might mean that they’ll get to bear witness to some extraordinary sunrises and sunsets thanks to the way the dust scatters light. Those with asthma might want to take extra precautions as fine particulate can fill the air. Then again, these days many of us are wearing masks from the moment we step outside anyhow.

Original Post from this site